- More than 500,000 jobs lost in two years as factories close

- Improving power, gas supply may halt export drop: central bank

A neglected waiting area, empty reception and dim lights greet visitors at what used to be the biggest textile factory in the northern industrial area of Pakistan’s economic hub.

At its peak Al-Abid Silk Mills Ltd. employed 7,600 employees in Karachi, now only a handful can be seen in the near-abandoned garment workshop. It’s one of hundreds that have shut down over the past few years, contributing to Pakistan’s exports falling to their lowest in six years.

An abandoned textile factory.

Photographer: Asim Hafeez/Bloomberg

Exporters from South Asia’s second-largest economy, including textile manufacturers who account for more than half of all overseas shipments, say buyers have shifted to countries including Bangladesh and Vietnam as continual power outages impede their ability to meet order deadlines, while complaining that the government has provided scant support.

“The government has never planned how we need to go forward with the textile industry,” Naseem Sattar, the 80-year-old chief executive officer of Al-Abid, said as he smoked in his office in the derelict plant. “Such a factory is considered a national asset and we got no help.”

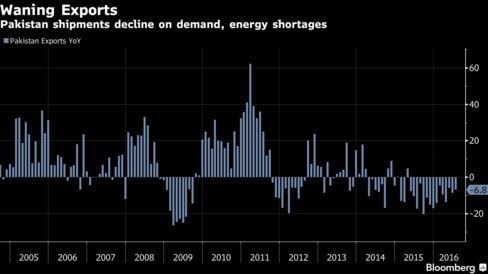

Despite a pick up in economic growth after the government submitted to an International Monetary Fund program in 2013 to avert a balance of payment crisis, Pakistan’s exports have fallen as global demand slows and the nation tries to overcome an energy shortage. Overseas shipments for the year through June fell to $21 billion, the lowest level since 2010, according to Pakistan Bureau of Statistics.

“Internally you have constraints on energy and then manufacturing keeping exports down,” said Turab Hussain, head of the economics department at the Lahore University of Management Sciences. “If oil prices go up and exports don’t pick up there will be pressure on your balance of payments and currency.”

About 100 member factories have shut down and at least 500,000 people have lost jobs in the past two years, according to Saleem Saleh, acting secretary general of All Pakistan Textile Mills Association, the biggest contributor to the nation’s textile exports. About two-thirds of the members of the Pakistan Bedwear Exporters Association have stopped working in the past five years, according to its head Shabir Ahmed.

Most factories shutting down are small or mid-sized plants unable to bear the extra cost of prolonged power outages. Meanwhile, larger factories have invested in their own power, including diesel generators, to cope with the nation’s electricity deficit of about 3,000 megawatts.

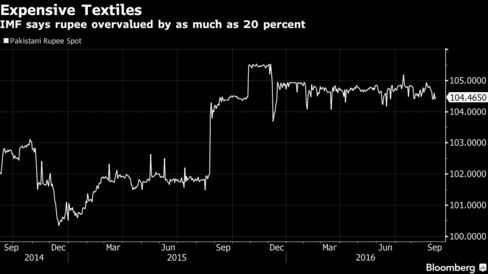

The IMF, which is set to conclude its three-year, $6.6 billion loan program with Pakistan at the end of this month, is pointing to a number of causes, including the local currency it says is overvalued by as much as 20 percent.

“The continued decline in exports is a cause for concern, to a good extent that’s due to a fall in international prices for cotton and other commodities,” Harald Finger, the IMF’s mission chief for Pakistan, said in a July interview. Domestically “there are security issues, there are continued power outages, even though they are declining now, that’s still a factor. There are issues around the business climate, and so on, and also one of these factors is also the real effective exchange rate.”

Yarn bobbins sit in a closed textile mill.

Photographer: Asim Hafeez/Bloomberg

About half of the Pakistan’s exports are shipped to six countries, while 40 percent of total textile exports are primary commodities, including cotton yarn sent to China, Minister of Commerce Khurram Dastgir Khan told lawmakers in Islamabad’s parliament on Sept. 5. Pakistan’s apparel exports grew less than half the pace of Bangladesh and Vietnam before the recent fall during 2005 to 2012, according to World Bank data.

For buyers, Pakistan’s competitors are also more alluring due to the country’s tarnished security image after years of insurgency, bombings and violence.

Security Perception

Even so, the country’s security situation has improved with an army push against insurgents after more than 100 students were killed by the Pakistani Taliban at a military school in 2014 in the northern city of Peshawar. About 449 people died in terrorist-related violence last year, the lowest in 10 years, according to the South Asia Terrorism Portal.

The government recognizes the industry’s malaise and Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif on a visit to Karachi on Sept. 8 said boosting exports is a top priority and his administration will soon announce relief measures.

‘Cannot Ignore’

Sharif is also pegging his 2018 re-election prospects on ending the daily power blackouts, relying on a surge of Chinese investment and projects worth $46 billion that were announced last year.

“Economic growth and exports are interlinked,” Sharif said. “We cannot afford to ignore our exports.”

A worker operates a sewing machine at a textile manufacturer in Karachi.

Photographer: Asim Hafeez/Bloomberg

Pakistan already announced in June azero-rated sales tax regime for five export industries, including textiles. Borrowing has become more attractive with the discount rate at its lowest in more than four decades. Sharif this month asked the ministry of commerce to arrange a duty-free import of five million bales of cotton to plug a domestic shortage this year.

Despite these measures, State Bank of Pakistan Governor Ashraf Mahmood Wathra says the nation needs to diversify products and exports markets away from those on a declining trend. However, he expects improved electricity and gas supplies this year to stem some of the drop in exports.

‘Very Happy’

“When I speak to industrialists, I see them more comfortable than two-to-three years ago,” Wathra said. Textile exporters complain about tax refunds being delayed by the authorities, but otherwise “they are very happy with the interest rate and refinance rate,” he said.

Sattar, whose factory used to make $100 million annual revenue at its peak, doesn’t agree. He wants to get his plant running again, but is unable to repay loans taken to purchase the milling machines. Sattar is now being hounded by banks and the country’s anti-graft agency, he said.

“If you are drowning, they push you further down,” he said. “Textiles are going away from Pakistan.”